Most language arts teachers start the new school year with a writing assignment about summer vacation. It is a fast and easy way to learn about a student both personally and academically. Making a small change in this assignment to make it more creative or unique will yield better results in the usual areas, but it can also make children excited about writing.

The Start

The first writing assignment of the year sets a precedent for the attitude of both teacher and student. Prompts generated by standardized assessment content creators are always random and uninteresting, and the stack of papers reflect that lack of connection. It is as painful for the teacher to read as it is for the students to write, and we’re all left with a sense of dread about the year ahead. When given the opportunity to reflect genuinely and in a creative way, students are more interested and engaged with their writing, and the stack of papers reflects the connection and liveliness of their authors. Suddenly the “work” becomes something to look forward to.

The Twist

The shift from standard prompt to engaging writing can be a small change in directions, or an entire modal shift. When we were starting with a creative writing unit, the prompt became one where the students had to use each of the five senses at least two times when describing an event that occurred over summer. A reminder of the five senses is helpful. When we were starting with a non-fiction unit, the directions included phrases like “write a memoir” and “this summer was the opening chapter to the book about your life”. This shift provides extra insight about how students perceive their lives, their dramatic flairs or their sense of humor, and it helps students think more positively about the non-fiction genre.

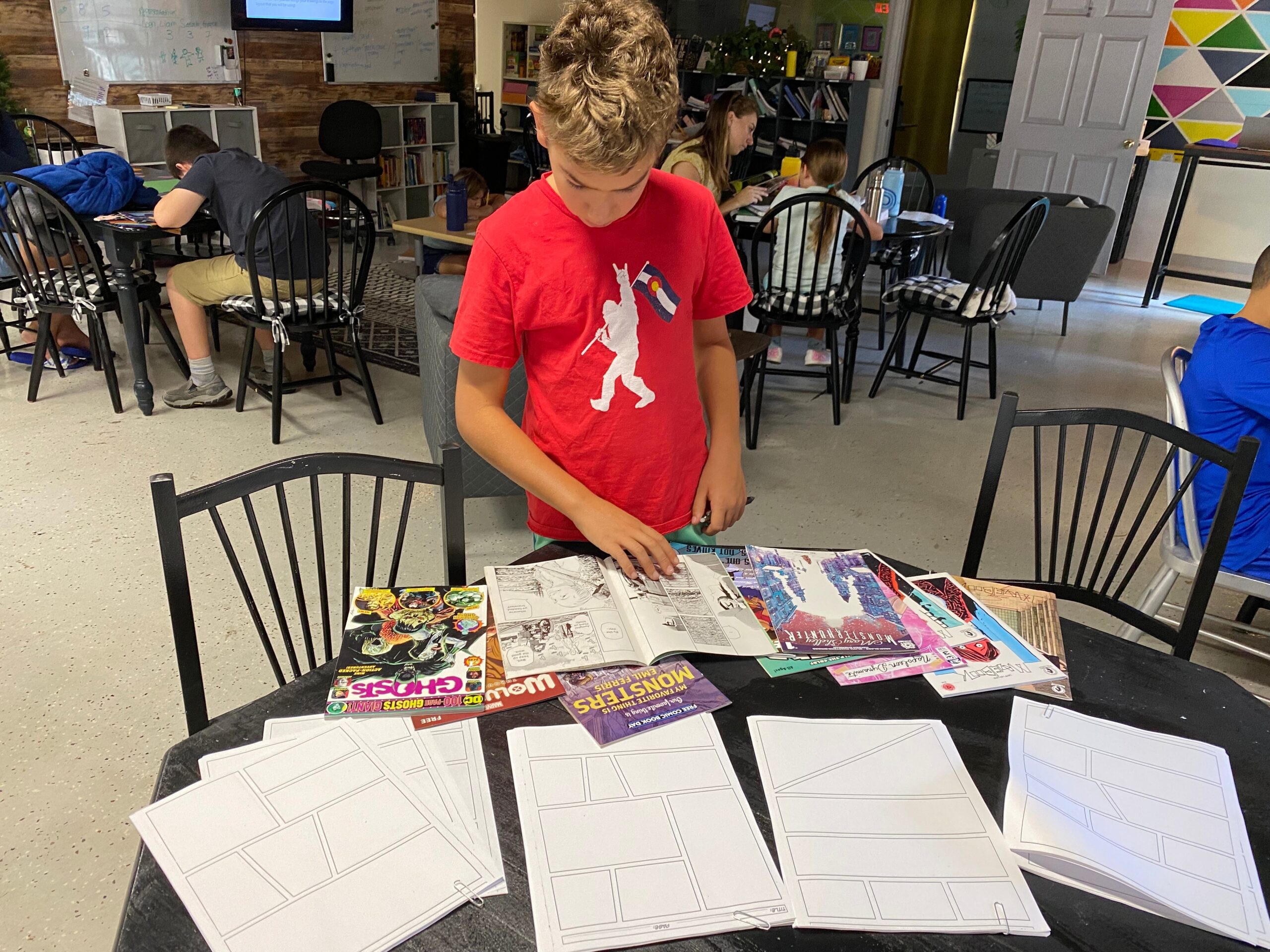

This year, I asked my students to write about one event that happened this summer in the form of a comic. I have quite a few artists and doodlers in my class this year, as well as students who struggle to write, and I’ll be incorporating comic books and graphic novels in my curriculum, so this became the perfect ‘twist’ for the typical summer assignment.

When told about this first big task, some students perked up right away: “I love comic books!” and “I only read graphic novels!” and “I already do that in my free time!” started bouncing off the walls. Other students had never read a comic strip in their lives, not even in the “funnies”. And, of course, there are students who “can’t draw”, “can’t write”, “can’t find one thing that would be a good comic story”, and in comes Growth Mindset! It wouldn’t be a start-of-the-year-writing-task if we didn’t have some “can’t”s and “hate”s, and many opportunities to embrace that room for growth.

We took intentional time to brainstorm the kind of events that can be portrayed visually (which turns out to be basically everything), to plot the main points of the story on a diagram, and to assign plot points to basic sketches. The final step was handing them their pages of blank panels and letting them make it their own. Some students changed the flow of how the panels should be read, others cut out the panels individually to rearrange them on a larger piece of construction paper, and a couple used applications to create their comic digitally.

Almost every student said that the task was harder than they anticipated, and almost every student was very proud of their final product. There’s always a perfectionist or two who think they could’ve done better. I am so proud of the students that “couldn’t write” who wrote captions for their drawings, and the students that “couldn’t draw” for stepping up their stick figures to what I called “sausage people”, or, stick figures with clothes and sausage fingers. Setting the expectation for this small amount of extra effort motivated students to pay extra attention to details in every other aspect of the assignment, and every comic turned out to be something we were all excited about.

The Takeaways

In addition to learning more about my students personally and academically, I gathered a few key take-aways from this version of the summer writing assignment:

One, students do not have opportunities to draw and color in an academic context beyond early elementary levels or individual units in an art class, which we’re seeing less and less of. Instead, drawing is seen as a distraction and coloring is seen as juvenile and kiddish, not something a ‘big kid’ would do. As a result, students are limited in their visual storytelling abilities, and their imaginations aren’t as practiced.

Two, this version of a summer writing assignment opened up pathways to concepts that we wouldn’t have discussed this early in the year, if at all in a ‘traditional’ ELA curriculum. Some questions that came up include “how do I show a party without drawing the same thing over and over?” and “how do I show a feeling?” and “how do I write something to tell what is happening and also what people are saying?”. We talked about visual storytelling and how we can recognize the passage of time, about how feelings can be represented visually and how people will interpret the same drawing or color in different ways, about the small differences in emotions, the word ‘nuance’, and the difference between narration and dialogue. Some of these conversations would have happened eventually, but the conversations and learning that occurred during this initial writing process was almost more valuable than their final product.

And finally, I learned how easy it can be to make writing fun. Even students that come to a language arts class as avid readers or creative writers, they still struggle with writing in academic settings. When a teacher incorporates creativity and choice into any task, engagement automatically increases. With increased engagement comes an improvement in effort, and then students become proud rather than resentful. Sharing becomes easier, and the excitement is contagious. And before you know it, we’re all looking forward to the year ahead.