The American education system has come a long way in the last two hundred years – at the height of the industrial era, schools resembled factories in order to efficiently educate a working class. The factory model for a classroom included putting students into grade levels based on age, desks were organized in rows facing the teacher, who oftentimes gave lectures as an efficient means of delivering instruction, and the focus was on students producing specific results.

John Dewey, a leading educational theorist at the time, insisted that this was not the way nor the focus that should concern a public school. Instead, groupings should be based on ability, and the goal of school should be to prepare students to fulfill their own greatest potential in order to participate successfully in democracy. Though this model was not adopted in the 19th century, and not widely accepted in the 20th century, I am happy to see some of Dewey’s pivotal ideas being implemented in the last 20 years.

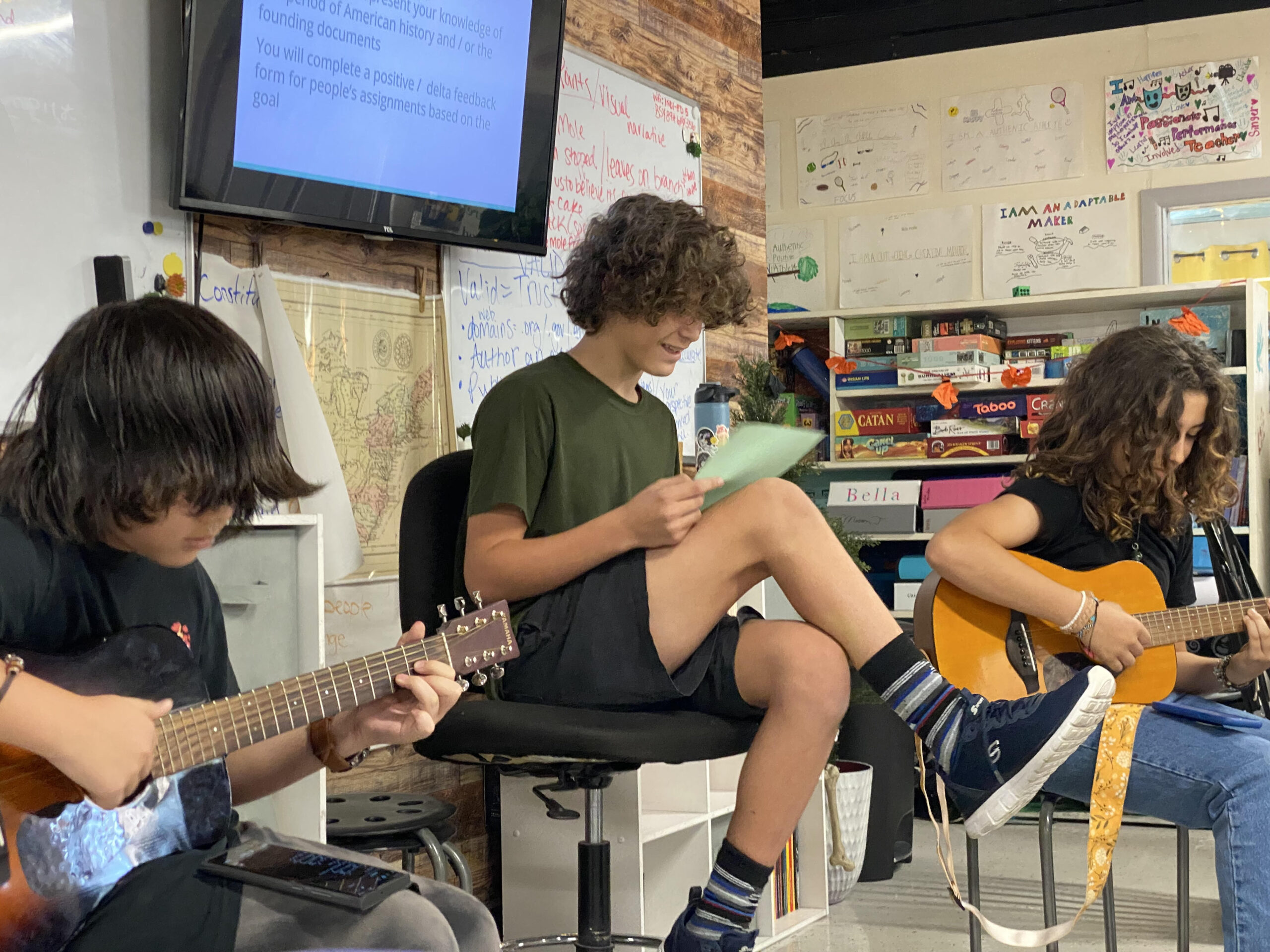

Here at Indi-ED, we agree that school should prepare students for life as well as the workplace. Our students are grouped into ‘cohorts’ based on a variety of factors including age, interest, and social-emotional maturities, and we put our students in charge of the learning so that they may stay engaged with the process rather than uninterested receivers of information. In this way, we are able to empower students to learn what they want, in ways that work for students of all abilities, and truly fulfill their potential as growing young people.

It is one thing when a teacher asks the students “what do you want to learn about”, to hear them say “animals” and toss in some books that have animals as main characters. It is another thing to know each student intimately enough to build a well-rounded ecology unit that has processes and structures in place for students to learn biological and environmental sciences, drive their own research about how man-made structures impact surrounding ecosystems, and make connections between individual animals and the planning and management of a city, all at levels that range from 3rd to 9th grade. Put together in this way, it sounds like a lot, but that is just one part of a teacher’s job at Indi-ED. We bring the students along with us during that process and empower them to take on as much researching, planning, and connecting as possible. Putting not only what a student learns, but also how they learn it, into their very capable hands, cultivates a level of depth and connection to learning that they certainly would not have while sitting in desks in rows ‘receiving’ information from a lecture.

But academic empowerment is not the only, nor even the most important skill that we focus on. I think the greater strength is our focus on social-emotional empowerment in the classroom. Students often arrive in our space with unique qualities and varying abilities – some walk in the door quoting Buddah and Voltaire at 10, while others at the same age might refuse to write a single word but can verbally express deep thought and connections at levels one might expect from a college student. And with such neurodiversity we often see serious levels of anxiety in our young people.

Call it the pandemic, call it ‘this generation’, call it whatever you will, but students that are walking through our doors in the last two years have had serious social and emotional anxieties that can limit their ability to fulfill that potential mentioned earlier. We just talked about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in social studies class, and a few students had “a-ha” moments when we discussed the need for safety and a sense of belonging before being able to self-actualize – if a student doesn’t know where they’re going to sleep that night, it is real hard to focus on multi-step algebraic equations; if a student feels like they are the only one that doesn’t belong in the class, they have a hard time dropping ‘everyone is staring at me’ thoughts and replacing them with understanding the nuanced language of the constitution.

Now that they know these levels of needs exist, it is easier for all of us to communicate with each other about what is missing. Instead of sitting and staring into space, stomach grumbling, a student might share with me that they are having a hard time focusing because they didn’t have breakfast that morning. Instead of being frustrated with a student that is doodling in the margins rather than writing, I can ask the student if something is bothering them and they might share with me that their recent dyslexia diagnosis is making them feel isolated from the rest of the class. Of course, this level of self-awareness and communication does not happen immediately because of one Maslow’s hierarchy lesson, but is possible with time, appropriate modeling of language and processes, and the flexibility of failure.

I am incredibly proud of the students that know when they are struggling, and why, and are able to ask for specific tools or processes to help them return from an anxious place into a productive one. I am also very proud of the students that don’t know exactly why they are struggling, but are working on it and are able to say “Ms. Shand, I’m having a hard time today.” Empowering students to not only understand themselves and their needs, but also to know what specifically will help them cope socially and emotionally, feels like magic.

Here is a link to understanding Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and some steps to take when working to empower your own children and students:

- Step 1 is telling them that they are in charge now

- Use the word “empower”, it will speak to their independence and help with self-confidence – “You’ve got choice A or B. I empower you to make the choice that best supports what you need right now.”

- Step 2 is showing them

- Using language to identify your own feelings & needs with students will model how you want them to communicate with you

- Give them resources to be in charge in small ways to start

- Gradual release from choice in overall topic, to choice within assignments, and eventually choice in processes will have them running their own classroom by the end of the year

- Step 3 is guiding them

- When moving to bigger tasks or projects, challenge their first idea

- As they learn more complex processes, be ready for repeating phrases like “did you remember to…” and “did you try…” and “what if…”

- Completing pre-planning and reflection activities are big parts of helping students see what went well and what could be done better next time

- Step 4 is positively acknowledging them

- Positive behavior reinforcement always, but especially when they are trying, and sometimes failing, at being in charge of themselves

- No one knows how they are feeling and why all of the time; give students room to feel and time to process while reminding them that you’re there when they’re ready

- Ask your students how they like to receive feedback and acknowledge them in the ways they want; true empowerment in the classroom can’t happen without this respect

We’re so lucky to be able to move, adjust, and do what is necessary quickly based on advancing research on learning and well-being for the kids who are in front of us and the moment of time that they are in. Watching them learn information about history, life, and themselves and how they can impact their own worlds-that’s the learning that is powerful.